From Hype to Hard Numbers: The True Scale of Ottawa’s New Housing Push

Introduction

The Liberal Government is in and we are starting to get more clarity on what that means for housing in Canada.

In our last article, we compared the

Liberal vs. Conservative Housing Platforms, and discussed how the majority of the Liberal housing platform would be positive for housing investors, but that the Build Canada Homes program had the potential to negatively overshadow everything else.

One month later, our opinion has softened. The limited documentation available about Build Canada Homes indicates that the government will be (directly) building far fewer homes than we initially anticipated, which has materially lowered our level of concern. Build Canada Homes looks to be far too small to displace private builders or upset private markets.

In this edition of the Bird’s Eye View, we review publicly available information on the Build Canada Homes program to determine its scale and potential impact. We then turn to the secondary question of how successful that program is likely to be as we review two of the models that the Liberals have used as inspiration for Build Canada Homes; the Wartime Homes Limited program that saw the Federal Government get directly involved in homebuilding post-WWII, as well as the Singaporean Public Housing model.

Build Canada Homes

“The Liberal housing plan will double Canada’s current rate of residential construction over the next decade to reach 500,000 homes per year”.

Liberal Housing Plan, March 31, 2025

We begin as we so often do with a caveat. It’s important to recognize that there is uncertainty about what this program will look like, as the entire housing plan (at least what is publicly available) is a mere two-page document. The truth is that we really don’t know what this program will look like, even if we know its goals and now have cost estimates.

Canada built ~245,000 homes in 2024, which is near the all-time high for annual construction (257,453 units were built in 1974). Getting to 500,000 units by 2036 feels like it borders on impossible, and is potentially much higher than what’s necessary.

When we saw the 500,000 homes per year target, alongside the words “deeply affordable,” and the announcement that “the Federal government will get back in the business of building homes”, we saw a very real potential for the heavy disincentivization of private development. If the government is going to compete with private industry while subsidizing costs, why would private industry build anything? Why would private investment fund it?

On further review, those concerns are now much smaller than we initially feared. Since we won’t see the 2025 federal budget

until the fall, we are limited to the

Liberal Housing Plan as well as the

Liberal Fiscal and Costing Plan to get a sense for the program itself and how much money the Feds will be allocating to it, but those documents indicate that funding allocations will be small.

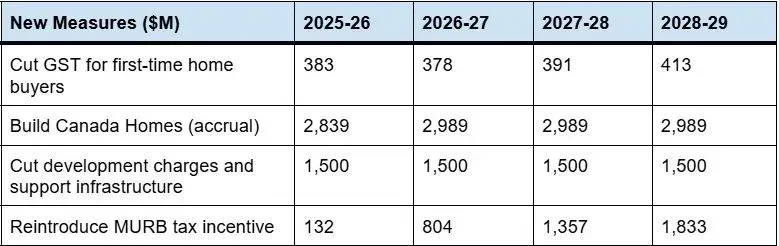

Here are some of the housing highlights from the Liberal Fiscal and Costing Plan:

Source: Liberal Fiscal and Costing Plan, Chart recreated by Hawkeye Wealth for legibility.

The full cost of housing initiatives, including GST cuts, DCC reductions, the new MURB tax incentive, and the Build Canada Homes program, is expected to fall between $4.9B and $6.8B in spending per year, while the Build Canada Homes portion is expected to cost ~$2.85B to $3.0B annually. With the 2024 budget at ~$449B, the Build Canada Homes program is smaller than we anticipated at 0.65% of the annual budget.

At the proposed funding levels, the Build Canada Homes program simply doesn’t have the funding to build an appreciable number of homes and displace private investment, which we see as a positive. At $250,000 per unit, the Feds could build ~12,000 (small) units per year with this funding. It’s not nothing, but it’s also only 2.4% of the 500,000 target, or ~5% of 2024 building levels.

Unless funding levels increase, we would be surprised to see more than 60,000 homes directly constructed by the government under the Build Canada Homes program over the next four years.

With the question of the size of the program answered, let’s look at whether Build Canada Homes is likely to be successful by reviewing the Wartime Homes Limited program, as well as the Singapore public housing model.

Wartime Housing Limited

“Mark Carney’s Liberals unveil Canada’s most ambitious housing plan since the Second World War.”

“Canada has solved a housing crisis before, and we can do it again”.

Much of the rhetoric around the Build Canada Homes plan is based on the Wartime Housing Limited (WHL) program, which has been credited for pulling Canada out of the 1940s housing crisis.

What might surprise you is that for all the hype, WHL only oversaw the development of 31,192 homes between 1941-1947. This represents approximately 8.2% of the total number of homes constructed during that time.

By most accounts, WHL was highly successful in achieving its mandate.

Jill Wade’s 1984 thesis paper details and evaluates the WHL program from when it began in 1941 to when it wrapped up in 1947, and we’ve provided highlights below:

- In the early 1940s, Canada experienced a housing shortage that stemmed from a lack of new supply built during the Great Depression, followed by labour shortages during wartime.

- The intent of the program was to build ‘temporary housing’ at the lowest possible cost and rent the homes to veterans. Homes were only intended to last 10 years, even though many of the units lasted far longer, and some still stand today.

- Panels were pre-fabricated, and workers needed ~16 hours (not a typo) to put up a small house. Neighbourhoods of 20 homes could go up in 30 days.

- The intent behind building ‘temporary’ homes was to keep permanent housing the purview of private development, so as not to disincentivize it.

Source: City of Kelowna, WHL Era Home (Built in 1946) - Kelowna, BC

- These units weren’t ever intended to be ‘subsidized housing’. Leonard Marsh, a program official stated that, “The corporation does not supply low-rental housing”, and that WHL had no intention of subsidizing its tenants, only building the lowest cost housing possible.

- Even in the WWII era, “many municipal governments reserved hostility, or at best passive tolerance for WHL projects”. The primary concern from municipalities was the perceived quality of WHL housing, as municipalities wanted more permanent (and more expensive) solutions.

- The program was largely successful at delivering low-cost, temporary housing, but once the war was over and the immediate need passed, the government privatized and sold most of the homes, and what didn’t sell was transferred to CMHC.

How will WHL differ from Build Canada Homes?

1. WHL homes were temporary and not subsidized.

- In contrast, we assume that all homes under Build Canada Homes will be permanent, and given the language that has been used around ‘affordability’, we anticipate that they will be subsidized to some degree. This is especially likely after hearing Housing Minister Gregor Robertson’s comments last week that ‘he doesn’t want to see home prices decline and that the Federal Government needs to focus on affordable housing’.

2. WHL era permitting was comparatively simple and build times were extremely short. The first National Building Code was adopted in 1941 to accompany the WHL building program (and along with it, the broad adoption of building permitting).

- Modern building codes, permitting and inspection processes aren’t conducive to speed, even when using partially pre-fabricated solutions.

- If the government is subject to the same planning and permitting queues as private industry, it will add to costs and timelines. If they aren’t, private developers will be furious.

3. Availability of land, particularly in urban areas.

- Modern projects will need to put more units on smaller footprints, as developable tracts of land, even federal lands, are increasingly rare and expensive in urban centres.

4. Much of the oversight on WHL projects was provided by voluntary committees that supported land selection, negotiation, tenders, etc. This kept costs down (until they started using more staff in 1945).

- In 2025, all of these functions would likely be paid, not volunteer.

5. During and after WW2, there was general agreement and support from municipalities regarding the necessity for federal intervention as a wartime effort, despite not being overly enthusiastic about WHL projects.

- Today, many municipalities are likely to be less enthused about federal intervention.

Government can implement the same strategy that it did in WW2, building the cheapest pre-fabricated buildings possible, but there are still challenges that exist today that either didn’t exist or were smaller in the 1940s.

We highly suspect that both government and hopeful citizens will be surprised at how expensive these units will be to build and buy. While new technology may drive efficiencies that we don’t account for, we think it will take considerable subsidization to hit an ‘affordable’ price tag.

Singapore Public Housing Model

Anytime public housing is discussed, Singapore is held up as the poster child of success. You’ve probably read Canadian news articles or social media posts about the Singapore public housing model, echoing common refrains like ‘if Singapore can do it, why can’t we’?

It’s true that Singapore’s public housing program has been extremely successful. With home ownership rates at 90%, it’s easy to argue that they’ve done many things right. The Housing and Development Board (“HDB”) has built 77% of the homes that Singaporeans live in today.

While there are some elements of the Singapore program that could likely be ported to Canada, there are fundamental differences between Singapore and Canada that would make implementation of a similar program much more difficult in Canada.

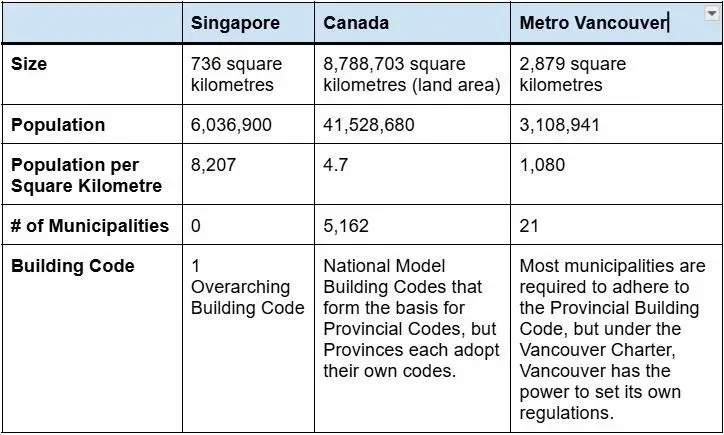

Here are some important stats that help paint a picture as to why Singapore’s program has been so successful, and why it might be more challenging in Canada:

Source: Statistics Canada, Singapore Department of Statistics, Metro Vancouver Regional District. Chart compiled by Hawkeye Wealth

Singapore is less than 1/10,000th the size of Canada, and is less than a quarter the size of Metro Vancouver. Setting up an effective public building program in an area smaller than Metro Vancouver, but with 8x more population density leads to incredible economies of scale efficiencies.

Couple this with the fact that the national government owns approximately 90% of all land in Singapore and that there is one building code and no municipal or provincial governments (just one national government), and you have a situation where the government controls its own development and permitting process entirely.

The 12-person HDB board is capable of having a high level of knowledge and oversight for all projects. Their manufacturing and design is for a single climate, and pre-fab solutions have minimal freight considerations. Highly skilled development and construction teams don’t have to be mobile, allowing deeper specialization.

In short, Singapore is a near perfect place to run a vertically integrated government housing system. In that context, Singapore’s policy decision to have the government become the main developer and run multi-billion dollar losses to build ~15,000 - 25,000 units annually is both wise and admirable. They only rely on private developers to build the much smaller proportion of housing types not provided by the Housing and Development Board (luxury homes, single family homes, etc).

By contrast, Canada is massive, has a huge variety of different climates that require different building solutions, along with inter-provincial variation in building codes. Public projects require coordination with 3 layers of government (as well as first nations in some instances), all with differing ideas, values and roles. The personnel structure that would be required to provide a similar level of local specialization and expertise across Canada would be enormous compared to Singapore.

Canada is not Singapore. If Canada tried to run an aggressive public housing program that in any way threatens private development, it would fail miserably. Thankfully, it doesn’t seem like Canada is moving that direction.

Conclusion

For investors, the majority of the Liberal Housing Plan is positive for investors, and the Build Canada Homes is the only item that has the potential to discourage private building and investment.

However, given that the Fiscal and Costing Plan preliminarily allocates only ~$2.9B to that program annually for the next 4 years, we think its impact on private markets will be minimal.

Despite its limited scope, we genuinely hope that the Build Canada Homes program is efficient and successful. That said, a modern WHL program would be much more costly and difficult to replicate in the current era, and there are enough differences between Canada and Singapore to believe that their model would also be much more costly here. Ultimately, Canada has an uphill battle to deliver cost-effective public housing.

The industry is a little nervous right now, and rightfully so given the current market challenges. But in our view, with the MURB tax exemption and DCC cuts around the corner, we believe the future is at least as bright as it was before the Build Canada Homes announcement.