Fee Simple Under Fire: The High Stakes of Aboriginal Title in British Columbia

“To a landowner, there is nothing more important than security of title. Once you have fee-simple title in B.C., it has to mean that land is your land. And that is very fundamental to our province – and in fact, to the country.”

- Niki Sharma, BC Attorney General

Introduction

How secure is property title in BC? The Cowichan Tribes v. British Columbia decision, released on Aug. 7, 2025 has brought that question into the open. It has sparked a storm of reaction and concern that goes far beyond the parcels in question in that case.

Land rights are a major part of where the rubber hits the road on the path to reconciliation, and if the public’s reaction to this decision is representative, it appears that support for reconciliation in BC runs right up to the line of private property, but not past it.

In this edition of the Bird’s Eye View, we examine this decision and what it means practically in both the short and long term, what the next steps will be, and how long it may take to get clarity.

Overview

In this

863 page decision, based on 5 years of trial involving 86 different lawyers, the B.C. Supreme Court declared that the Cowichan Tribes hold Aboriginal title to portions of their traditional village lands on Lulu Island in Richmond, which includes not just Crown lands, but areas that are held in fee simple.

The Court held that Aboriginal title is a senior interest to fee simple title, and that it “lies beyond the land title system in British Columbia”, which negates land title defences.

The Court declared that Canada’s and Richmond’s fee simple interests are “defective and invalid” (excepting one property). Regarding the properties owned by third parties, the Court directed BC to negotiate in good faith regarding those fee simple interests.

Additional Reading:

If you are looking for a general summary of a situation,

the letter sent out by the City of Richmond is a good starting point.

If you want more information about the specific legal arguments and defences that were advanced,

Cassels, and

BLG (among many other law firms) have provided excellent summaries.

What does this decision mean practically?

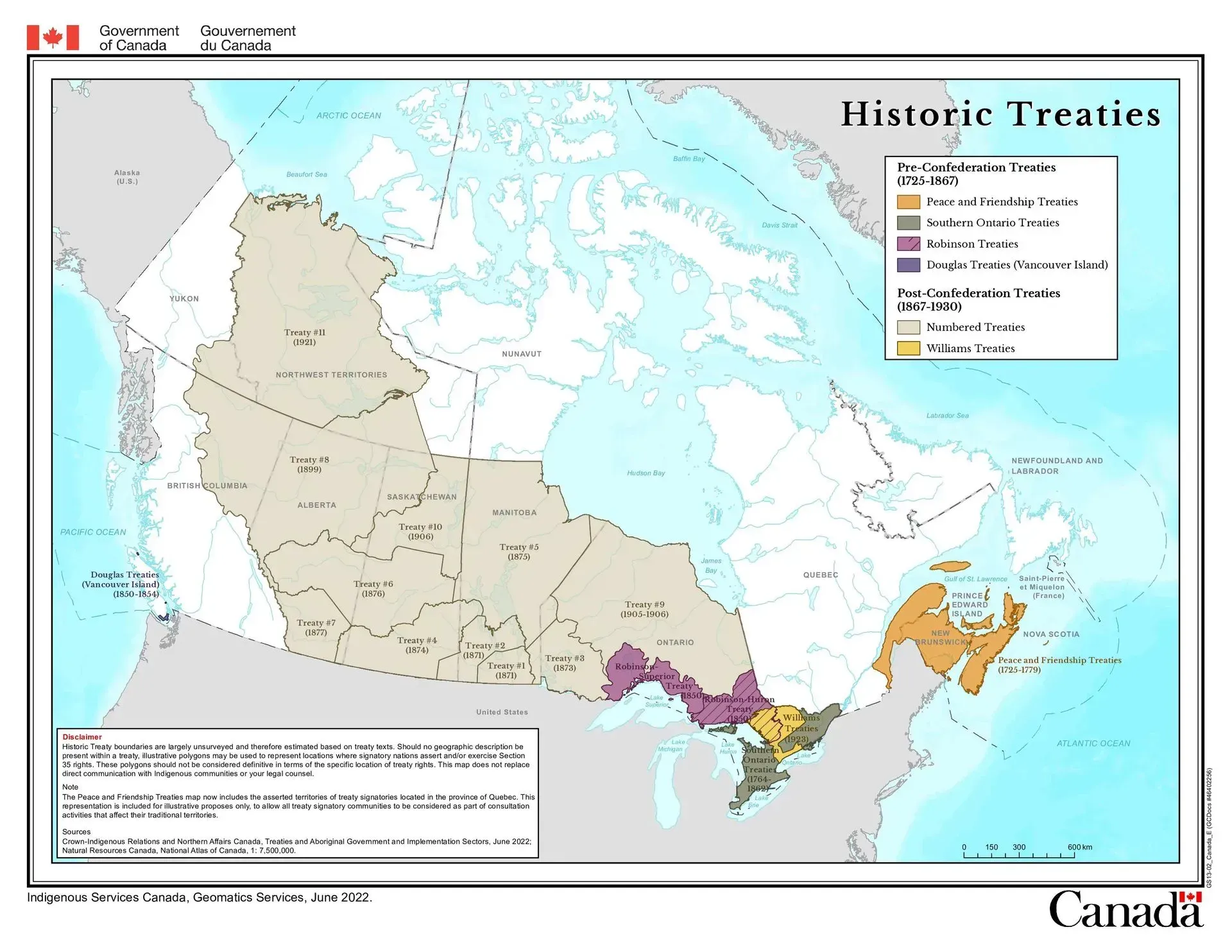

The effects of this decision, and any appeals that follow, will primarily be felt in BC and Quebec, since those are the two Provinces that mostly aren’t covered by treaty, as shown on the map below (land in white is not covered by treaty):

Source: Government of Canada

While there is nuance to this position, the primary effect of Canada’s historic treaties was the surrender or extinguishment of Aboriginal title to the Crown in exchange for reserve lands, annuities and other rights. This functionally means that at least in regards to this particular issue, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, and most of the Maritime provinces are more insulated from claims that Aboriginal title supplants fee simple title.

On the other hand, in BC, Quebec, Newfoundland and portions of the Territories, where Aboriginal title was never ceded, this decision and subsequent appeals will have a critical impact.

Who will bear the effects in the interim or if the decision stands?

While private property owners in the subject area are rightfully worried, we anticipate that senior levels of government would bear most of the immediate effects of this judgement, particularly in the long-term. That said, even if property owners are shielded from direct loss, taxpayers will ultimately foot the bill.

In the area in question in this case, it seems clear that the intent isn’t to take control of those properties, but instead seek some form of compensation from the Province for them.

In their

October 27, 2025 statement, the Cowichan Tribes said, “To be clear, the Quw’utsun Nation's court case regarding their settlement lands at Tl’uqtinus in Richmond has not and does not challenge the effectiveness or validity of any title held by individual private landowners. The ruling does not erase private property.”

They continued to say, “If any individual private titleholders at Tl’uqtinus are concerned about somehow suffering a loss, they should know their remedy is against British Columbia, the party responsible. It is not to get involved in the Quw’utsun Nation case.”

It’s wishful thinking that British Columbians won’t be keenly interested and increasingly vocal about this case, because speaking plainly, the vast majority of the Province is potentially subject to Aboriginal title claims.

Proving Aboriginal title isn’t a simple process, and it’s highly unlikely that it will be proven in all or even most areas. That said, if the requirement moving forward is to pay compensation (even at heavily reduced values) for all fee simple title properties in areas where Aboriginal title is proven, it will forever cripple a Province that is already struggling economically.

In the meantime, we don’t think anyone knows the full impacts of this decision. There have been rumblings about refinancing processes being held or cancelled, but to date, there is no concrete evidence for that (National Bank denied that this case was a factor in their $100M financing decision).

The Province knows that it needs to do whatever it can to ensure confidence in indefeasible title. Institutions are likely to conclude that either the Province will win on appeal, nullifying the concern, or it won’t and it will have to compensate the Cowichan Tribes on behalf of property owners, but it’s hard for us to picture a world where individual property owners are left holding the bag.

Timing

Certainty is coming, but not soon.

The Federal and Provincial governments, as well as the City of Richmond have indicated their intent to appeal this decision. Regardless of the outcome at the BC Court of Appeal, it’s highly likely that this case will rise to the Supreme Court of Canada. Given the time required so far and the overall importance of the issue, it will be many, many years before this litigation comes to an end.

In our view, this situation creates separation between the question of what is right and what is feasible. While courts go through the multi-year appeal process focusing on the question of what is right, governments will simultaneously need to review legislation and policy as it pertains to reconciliation, consultation, and land title with consideration to what is feasible.

We fully anticipate that this will continue to be a leading theme for the next decade, and while the process hurts, it is a necessary step towards a decisive answer to the question of whether your property is really yours.

Conclusion

The Cowichan decision marks a turning point in how Canada approaches the intersection of reconciliation and property rights.

For British Columbia, the stakes are immense. Both housing and commerce depend on the legal assumption that fee simple title is final. If that assumption weakens, even in narrow cases, confidence in the entire system is tested.

The legal process will take many years, and if the government does end up losing, we anticipate that they will step in to shield individual property owners from direct loss, but that protection doesn’t come without cost. If Aboriginal title is proven across larger swaths of the Province or involves significant urban lands, the financial burden could be extraordinary.

For us, this is one more factor that could detract from investment in BC at a time when that investment is sorely needed. We will be watching this case unfold closely.