The Affordability Conundrum: Supply Without Returns

Capital doesn’t flow to markets where demand is slow and supply is surging, it goes to places where demand outpaces supply and prices are rising. That’s not a flaw, it’s the system working as designed, rewarding investment in those markets that most need it.

Introduction

On paper, the cure for unaffordable housing is simple: build more.

In practice, the very act of building undermines the incentive to keep building.

The federal government has set a target of 500,000 new homes per year by 2035, but supply follows returns, not political will. As more units come online, margins shrink and investors retreat, a dynamic made worse by slowing population growth.

In response, experts across Canada have signed competing open letters and budget submissions, each offering prescriptions for how to restore affordability.

In this edition of

The Bird’s Eye View, we explore the widening gap between Canada’s housing ambitions and the market realities on the ground. We look at why supply targets are so difficult to reach, how policy prescriptions diverge between advocates and developers, and where governments may need to adjust course to bring targets and incentives into alignment.

The Scale of the Challenge

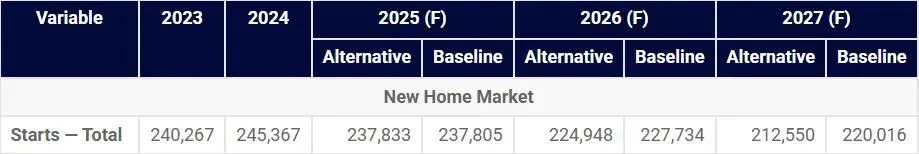

By 2035, the federal government wants to see 500,000 new homes started each year (Source). CMHC estimates that for that same year, between 430,000 and 480,000 annual starts will be needed to restore affordability to 2019 levels (Source). Hitting these targets means roughly doubling today’s pace of 245,367 starts.

The critical, often unstated requirement behind these supply targets is profitability.

If projects don’t offer an attractive risk-adjusted return, they simply won’t get built. That challenge is already visible in Vancouver and Toronto, where housing starts are down because many projects just aren’t worth the risk of building for the returns projected.

In the CMHC’s Housing Market Outlook Summer Update, CMHC cut housing start forecasts for every year from 2025–2027, with the 2027 baseline revised downward by 5.5% only five months after the previous forecast:

Source: CMHC Summer Update - Housing Market Outlook

Reaching 500,000 homes is straightforward to state, but financing that scale is another matter.

When Ambition Meets Demographics

To understand why the 500,000 target will be so difficult to hit, it helps to look at the supply and demand equation.

Statistics Canada projects that Canada’s population growth rate is forecast to slow sharply in the coming decade, from 1.5% annually from 2014 - 2024 to just 0.6% from 2025 - 2035 (Source). In other words, Canada is planning to double housing construction during what projects to be the weakest demand growth decade in Canada’s history.

Capital doesn’t flow to markets where demand is slow and supply is surging, it goes to places where demand outpaces supply and prices are rising. That’s not a flaw, it’s the system working as designed, rewarding investment in those markets that most need it.

The challenge with the 500,000 homes target is that it creates an intentional oversupply scenario that makes investment inherently unattractive. Why would developers start, or investors fund projects when price growth is projected to be weak or potentially negative? As it stands, they won’t.

If Canada wants to hit 500,000 new homes per year, policy is going to need to do some heavy lifting in order to change the investment equation.

The Policy Balancing Act

The aim in policymaking is to solve a problem without creating new ones.

Governments try to design measures that are just broad enough to hit the target, while limiting unintended negative effects. The public sector’s typical caution sharply contrasts with the urgency required for a 500,000 home target.

In fairness, the federal government has introduced numerous initiatives to bring down housing costs and expand non-market supply (Canada Housing Plan). These may be enough to keep today’s pace of development steady despite slowing demand, but it is hard to see how they would double construction within an intentional oversupply scenario. Canada will soon need to either scale back its target or accept policies that involve sharper trade-offs.

Recent advocacy highlights this divide:

One camp, a group of BC Housing advocates, argues that supply doesn’t automatically translate to affordability. They call for abandoning supply interventions altogether and doubling down on non-market housing (BC Housing Advocate Open Letter).

On the other side, the Large Urban Centre Alliance, representing some of Canada’s largest developers, warns that building won’t accelerate unless costs come down, proposing tax relief, financing support, and pre-sale rule changes to make projects more viable (LUCA Budget Submission).

We will not detail every recommendation here, but two points are worth examining:

1. Supply ≠ Affordability

We agree that supply alone doesn’t guarantee affordability. The evidence presented on that point is sound, as Vancouver’s housing stock has grown much faster than population, yet affordability has worsened.

However, the next leap from ‘supply doesn’t guarantee affordability’ to ‘non-market housing is the solution’ doesn’t work.

Non-market housing makes up ~3.5% of housing units in Canada (source). Expanding that figure would help the most marginalized households, but focusing on this segment while neglecting market housing will leave the vast majority of Canadians without affordability relief. Surely the goal is to restore affordability so that fewer people, not more, need to rely on non-market solutions.

2. Developers and the Investment Equation

It’s easy to read the Large Urban Centre Alliance submission and conclude that it is self-interested. Yes, many recommendations shift costs to government or buyers.

Yet these are exactly the types of measures that the government will need to implement if it wants to hit its 500,000 target. This isn’t about greed, but about explaining why starts are falling and what must change

We think it’s likely that if the federal government gives serious consideration to these proposals, offering tax reductions beyond those already proposed, there will be accompanying mechanisms to ensure savings are shared with end users. If designed well, there is a workable trade-off to be had: tax reductions that encourage supply and reduce project risk paired with policy guardrails that may limit the upside for developers but support greater affordability.

Both letters ultimately focus on shifting costs around the system to improve affordability. That is a necessary conversation, but it does not address the deeper challenge: the fundamental cost of building itself. Without tackling the drivers of construction cost, Canada risks creating a housing strategy that redistributes costs without ever reducing them.

Reducing Fundamental Building Costs

One of the clearest opportunities to reduce fundamental building costs lies in revisiting Canada’s building codes. While codes are primarily a provincial responsibility, the federal government plays a role through the National Building Code and could use that influence to encourage reforms.

Successive increases in energy efficiency, seismic, and accessibility requirements have all added cost and complexity, pushing more projects to the edge of viability. These standards each serve important goals, but collectively they raise a difficult question. Have we struck the right balance between safety, sustainability, and affordability?

Building codes that continually raise requirements without regard to cost are slowing construction and making homes less affordable. Given the scale of today’s housing crisis, this is a conversation Canada can’t afford to avoid.

Conclusion

Canada’s affordability challenge is not for lack of ambition. Ottawa has set bold targets, but in a market-driven system supply follows returns, and returns shrink when demand slows and supply rises. The 500,000 home target asks developers and investors to build into an oversupply scenario that makes projects unattractive unless policy changes the math.

Advocates are right that supply alone doesn’t guarantee affordability, but non-market housing cannot scale to meet the needs of most Canadians, so improving market affordability remains critical.

Developers are right that costs must come down. The cost-shifting measures they propose are the types that government will need to implement if it wants to hit supply targets. Rather than rejecting them outright, there is opportunity to structure those policies so that a lower cost of building translates into sufficient risk-adjusted returns for developers and real affordability for buyers and renters.

Affordability will only improve when ambition, policy, and incentives point in the same direction. Until then, 500,000 starts will remain a target on paper rather than a path in practice.