How Development Charges Are Pricing New Buyers Out of Homes

“The provincial government has provided local government with only two options to build infrastructure: development cost charges and property taxes. And I will always be on the side of property taxpayers, and we will look for developers and ‘growth to pay for growth’ as a principle.”

Introduction

This Mayor’s sentiment represents a long-standing consensus among many elected officials. The logic is intuitively appealing. Existing homeowners shouldn’t be burdened with the costs of new infrastructure. The result is that over the last decade, municipalities have aggressively increased development charges (DCCs) with the assumption that these costs are borne by developers.

However, the current housing crisis is forcing a necessary re-evaluation of this approach. As housing starts continue to slow, it is becoming clear that in a weak market, high development charges are a tipping point that is causing project pro-formas to fail.

Governments are beginning to acknowledge this friction. For some housing types,

Mississauga has eliminated development charges, and drastically reduced them for all others.

Vancouver and

Hamilton have temporarily reduced development charges by 20%. At the

Federal level, the government has linked $17.2B in infrastructure funding to development charge reform, requiring municipalities to substantially reduce development charges to qualify for funding.

While these policy shifts aimed at increasing supply are important and welcomed, the CMHC’s recent paper, “Who Bears the Cost of Growth?”, may have delivered the data-backed death knell to the ‘growth pays for growth narrative’.

In this edition of the Bird’s Eye View, we highlight the CMHC’s key insights that suggest that these charges haven’t just hindered supply, they have functioned as a massive, unintended wealth transfer.

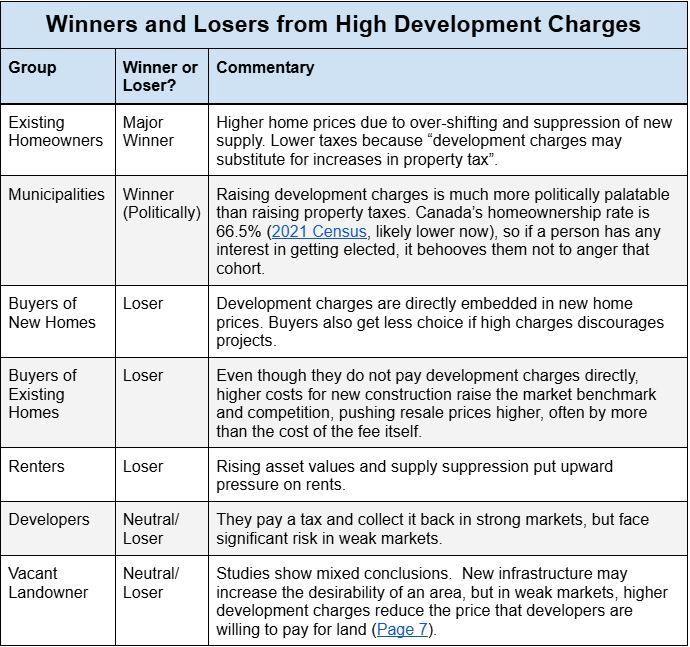

The Winners and Losers with Development Charges

The intention behind the ‘growth pays for growth’ slogan is making sure that developers pay for the full cost of their developments and associated infrastructure, so that the burden doesn’t fall to existing taxpayers. On paper, it’s a perfectly reasonable proposition, but there are three reasons that levying development charges don’t achieve their intended aim:

1.

Developers don’t pay, new buyers do

As CMHC notes on page 4, when markets are strong, developers pass the costs of development charges along to purchasers in the form of higher prices. When markets are weak and developers are unlikely to generate reasonable returns, they simply choose not to build.

2.

Development charges increase housing costs by more than the amount of the charge

For new housing, CMHC concluded that “the transmission to new house prices is typically proportional to, but often greater than the size of the development charge. This markup may account not only for the fee itself but also for associated financing costs and administrative overhead associated with the fees.”

The even more insidious effect is that the same holds true for the resale market. Studies suggest that each additional dollar of development charges can increase the price of existing homes (which aren’t subject to development charges) by between $1.00 and $1.68. This over-shifting effect comes as buyers priced out of new construction compete more aggressively for resale housing.

While we don’t know the actual multiplier in any given market, we can look at an extreme example like Markham to understand the potential impacts. There, DCCs represent

15.7% of a new condo’s price. When considering the multiplier identified in CMHC’s research, DCCs likely account for between 15.7 and 26.4% of the price of

existing condos

in that community. In other words, a quarter of a home's value in that community may be explainable by municipal fee policy alone.

3.

Suppression of New Supply

If development charges are too high, some new projects don’t move ahead. This reduces future supply, which increases the premium of all existing homes in that municipality.

CMHC’s conclusions make the distributional effects clear:

Source: Table created by Hawkeye Wealth, based on CMHC findings

Striking a New Balance

To be clear, we aren’t advocating for the total abolition of development charges. They have been used in Canada since the Second World War, and have long served their primary purpose of funding essential infrastructure that requires upfront capital and purposeful overcapacity relative to current needs. Without development charges, existing property owners would carry an unfair proportion of new development costs.

It is the recent overreliance on development charges as a primary infrastructure funding mechanism that has caused market distortions, particularly in BC and Ontario.

The issue is one of balance. By raising development charges to unsustainable levels, we have effectively asked the next generation of homeowners to subsidize existing owners; a policy that doesn’t make any sense given the tough financial reality for many young families. Governments face the challenging task of finding equilibrium between their infrastructure needs and those of both existing and new homeowners.

What does all this mean for investors?

As the "growth pays for growth" myth begins to crack, we expect to see a shift in the municipal fiscal landscape towards reducing DCCs and increasing taxes, though the timeline for implementation could be gradual. We anticipate three primary effects from this shift:

1. Improved project feasibility - Reductions in DCCs will likely bring some marginal projects back to the table, but there are enough other barriers, both in terms of cost and demand uncertainty, that it may take cuts in excess of the 20% proposed in Vancouver to really move the needle.

2. Property tax normalization - If DCCs come down, we think it’s likely that property taxes will rise eventually. Investors should prepare for slightly higher operating expenses, which would affect net operating income, though this may be offset by a more robust and liquid housing market.

3. Price normalization - There is a case that at least some of the price appreciation since 2020 has been induced by DCC increases. We expect that reductions in DCCs may cause price decreases. This would be a welcome trade-off for new development, but could make value-add strategies less attractive.

Conclusion

The debate over development charges is less about infrastructure and more about the politics of picking winners and losers. The CMHC’s research makes it clear that the loser has rarely been the developer, and it has consistently been the aspiring homeowner, a group that most policymakers would agree is in need of help.

Reducing DCCs won’t solve the housing crisis overnight, largely because hard costs remain a significant hurdle to supply, but it would make a meaningful difference towards making the math work again, both for developers and new buyers.

As the ‘growth pays for growth’ consensus continues to crack, we expect the pace of DCC reform to accelerate, particularly in BC and Ontario. At Hawkeye, we view this shift as a net positive. While it may mean higher property taxes and normalization of resale prices, we will always prefer a market where value is driven by operational excellence and market dynamics rather than municipal fee policy.